From sensors to wires. The next integration of publications will focus on our Nervous System and its multiple divisions. From everyday movements to life-or-death reflexes, the nervous system is the hidden electrical grid that keeps us alive. To understand it, we can divide it into two main hubs: the Central Nervous System and the Peripheral Nervous System.

For more information on the functionality of the neuron, feel free to explore our simple 3D model here.

“I asked an invertebrate to stand up for itself… but I guess only vertebrates have the backbone to do it.”

Central Nervous System (CNS): The Body’s Control Hub

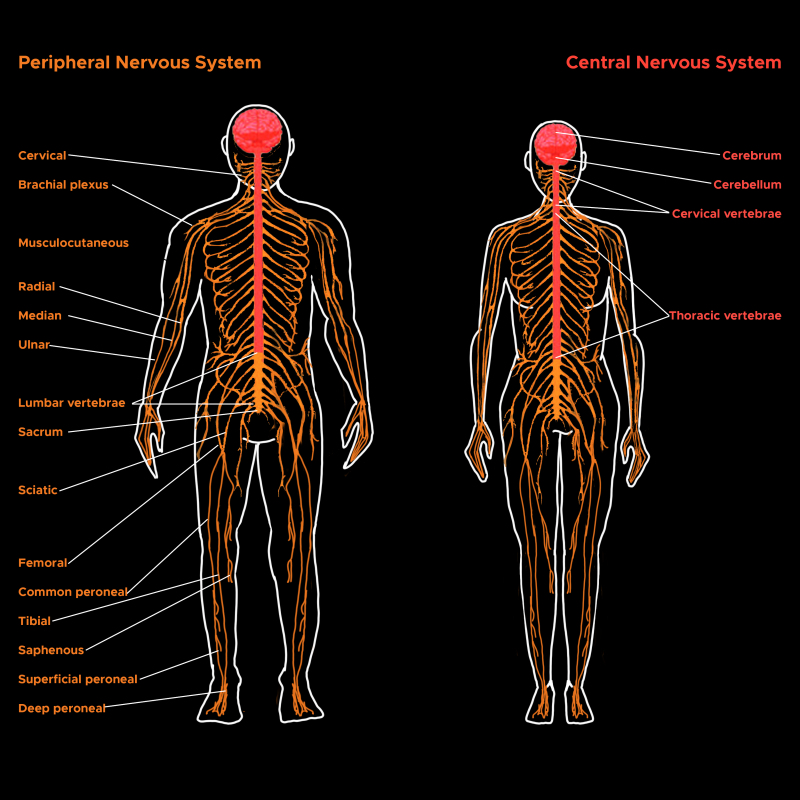

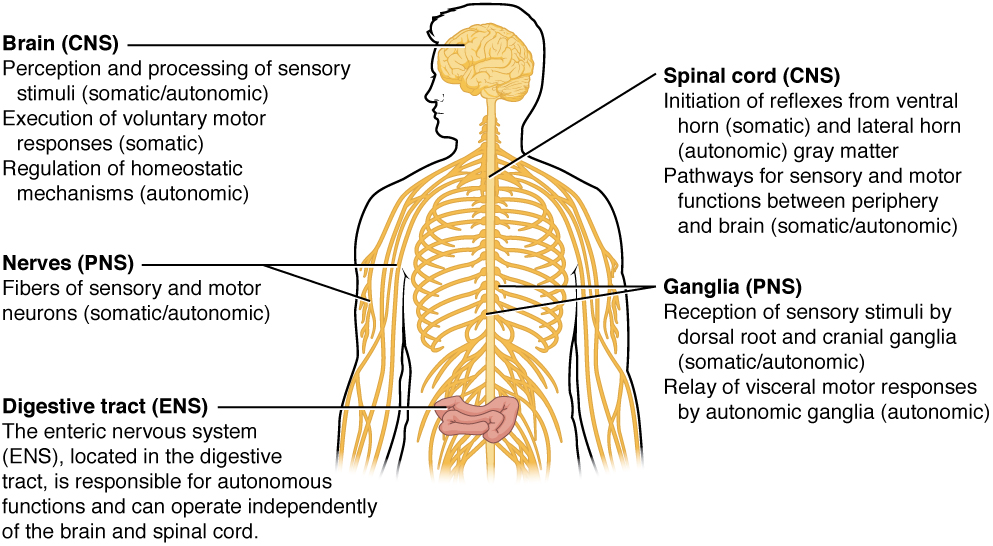

The CNS, made up of the brain and spinal cord, is the foundation of the nervous system. It processes information from the environment and coordinates responses, such as moving your muscles or maintaining balance (Ludwig et al., 2017).

The spinal cord acts like a highway, receiving sensory information from the PNS (e.g., the feeling of a hot surface) and sending it as nerve impulses to the brain. The brain then processes this information using specialized regions. For example, the cerebellum helps coordinate movements like walking, the thalamus regulates sleep and alertness, and the cerebrum—the brain's outer layer—handles complex tasks like thinking and decision-making. Cranial nerves, originating from the brain stem, control automatic functions like eye movement and facial expressions. We will explore spinal and cranial nerves much more in depth in later publications but are worth mentioning in this chapter.

Peripheral Nervous System (PNS): Connecting Body and Environment

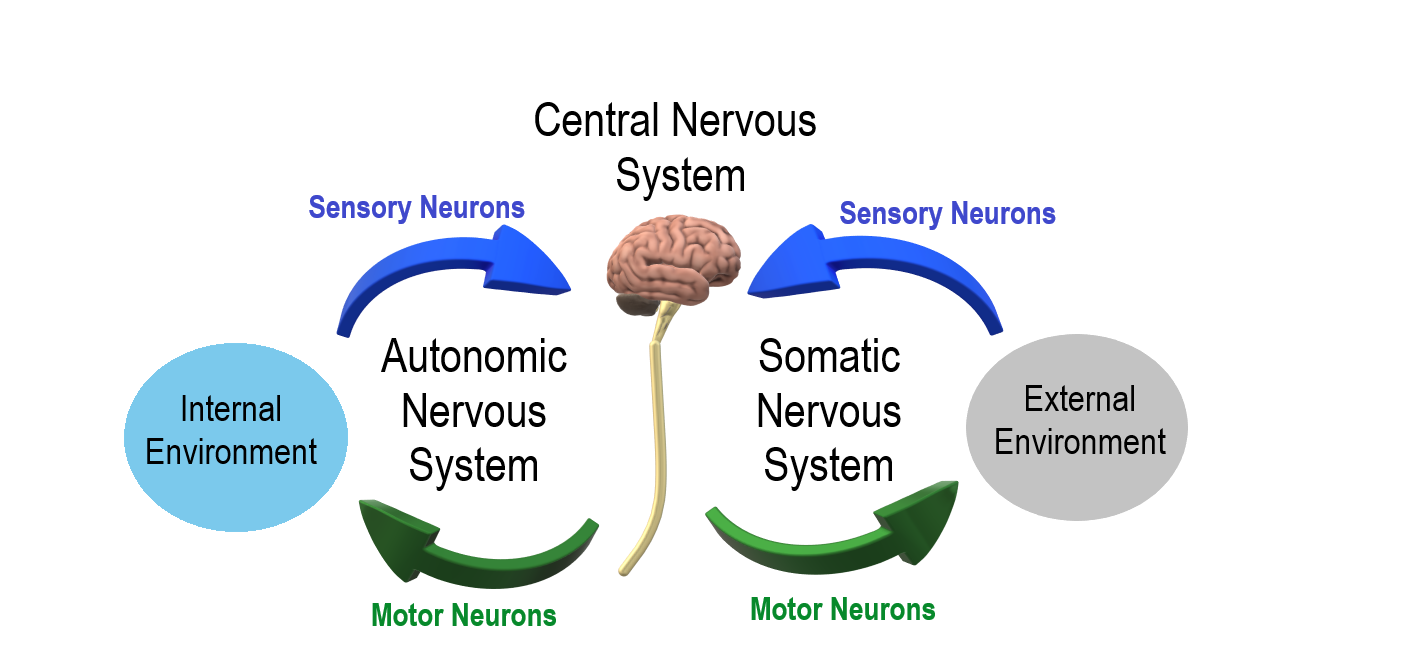

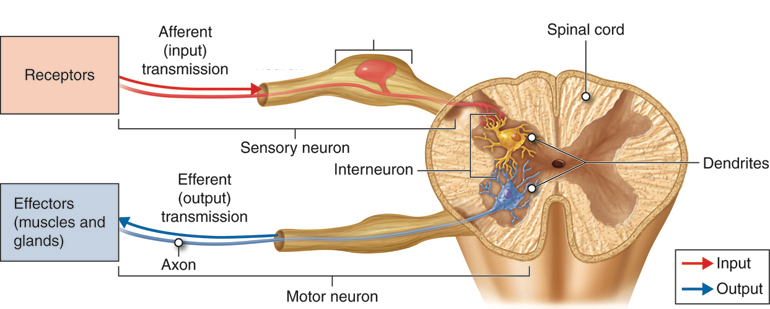

The PNS links the CNS to the rest of the body, enabling interaction with the environment (Catala & Kubis, 2013). It consists of sensory nerves (afferent, or “receivers”) that detect stimuli like touch or temperature, and motor nerves (efferent, or “transmitters”) that carry commands to muscles. The PNS is divided into two subsystems: the Somatic Nervous System (SNS), which handles voluntary actions, and the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS), which manages involuntary processes.

Somatic Nervous System (SNS): Sensing and Moving

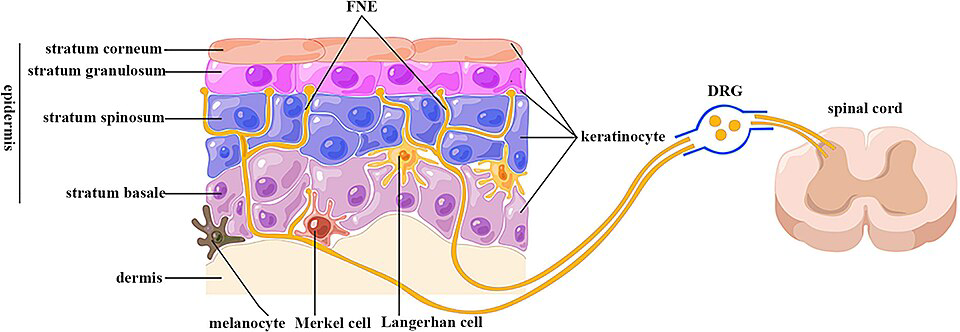

The SNS controls voluntary actions, like walking or picking up an object, and processes sensory information from the skin, muscles, and organs (Catala & Kubis, 2013). Sensory nerves, located in bundles called dorsal root ganglia near the spinal cord, relay information about touch, pain, or temperature to the CNS. For example, when you step on a sharp object, the SNS quickly sends this signal to the brain, prompting you to lift your foot.

Autonomic Nervous System (ANS): The Body’s Autopilot

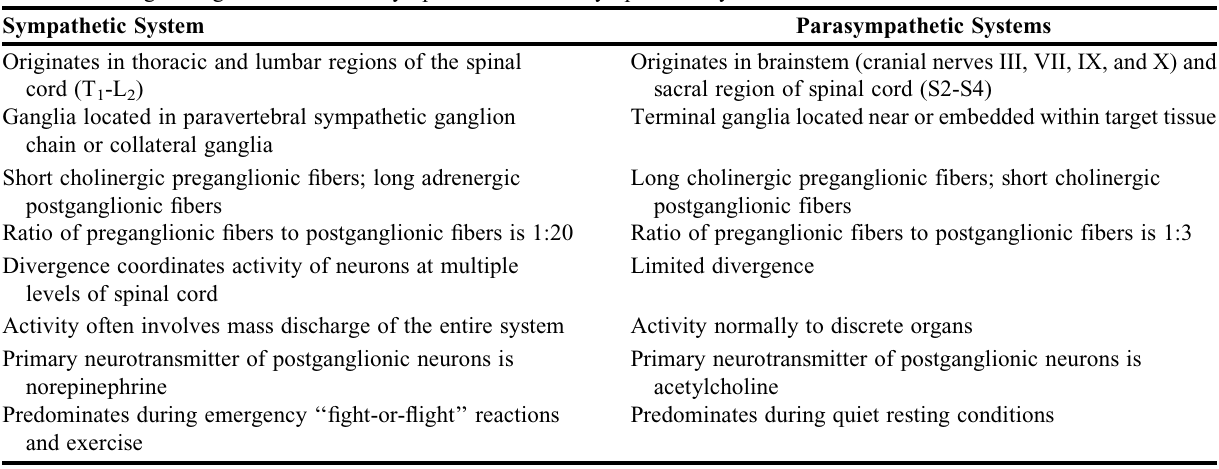

The ANS operates involuntarily to maintain the body’s balance, or homeostasis (McCorry, 2007). It regulates critical functions like heart rate, digestion, blood pressure, and body temperature. For instance, when you’re nervous, the ANS increases your heart rate to prepare you for action. The ANS has two branches: the sympathetic system, which activates the “fight or flight” response, and the parasympathetic system, which promotes “rest and digest” activities (McCorry, 2007).

The Enteric Nervous System (ENS) – The “second” brain

The ENS is considered a division of the ANS and has approximately 100-500 million neurons embedded in the walls of the gastrointestinal tract, from the esophagus to the rectum. Grouped nerve-cell bodies are bundled up together into small ganglia in the gut, forming two major plexuses (electrical junction box), the myenteric (or Aurrback’s) plexus (network of nerves) and the submucous (or Meissner’s) plexus. The ENS includes sensory neurons, interneurons, and motor neurons, forming reflex arcs that operate independently, much like a standalone system, which communicates with the CNS via the vagus nerve and sympathetic, allowing the brain to modulate gut functions (e.g., stress affecting digestion). This integration places it under the ANS umbrella (Goyal & Hirano, 1996). For example, the ENS can trigger digestive issues when you’re stressed, showing its link to the brain.

References

- Catala, M., & Kubis, N. (2013). Gross anatomy and development of the peripheral nervous system. Handbook of clinical neurology, 115, 29-41.

- Goyal, R. K., & Hirano, I. (1996). The enteric nervous system. New England Journal of Medicine, 334(17), 1106-1115.

- Ludwig PE, Reddy V, Varacallo MA. (2017) Neuroanatomy, Central Nervous System (CNS). In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL); 2025. PMID: 28723039.

- McCorry, L. K. (2007). Physiology of the autonomic nervous system. American journal of pharmaceutical education, 71(4), 78.