Electrical pulses are the key.

As you read, light from your screen scatters photons into your environment. These photons pass through your eye's lens, projecting onto the retina's photoreceptor cells, which convert light into electrical signals. These signals travel through the optic disc to the brain, where neurons process them to create your perception of this text. (For more information, see our Perception – Sight publication).

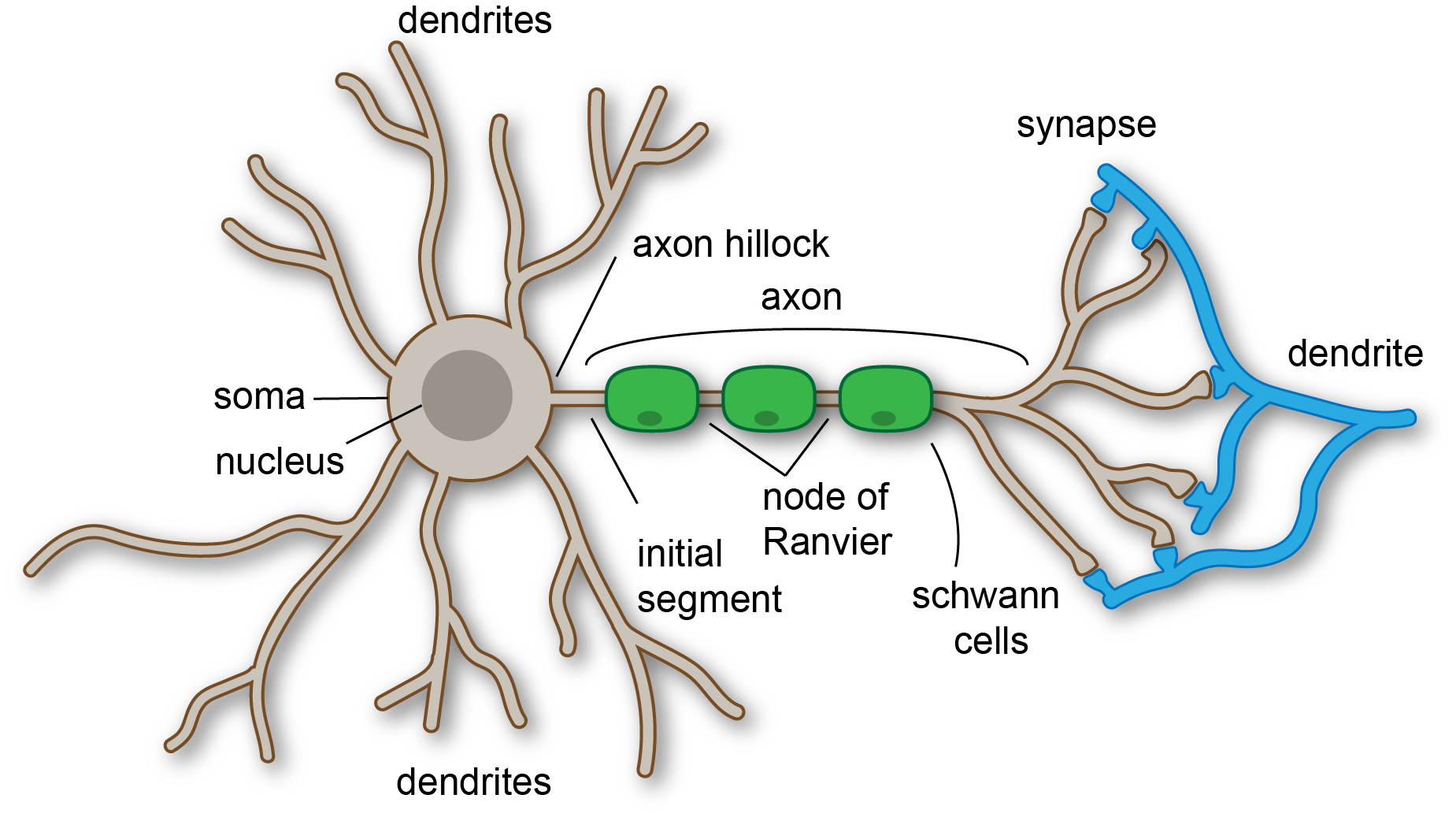

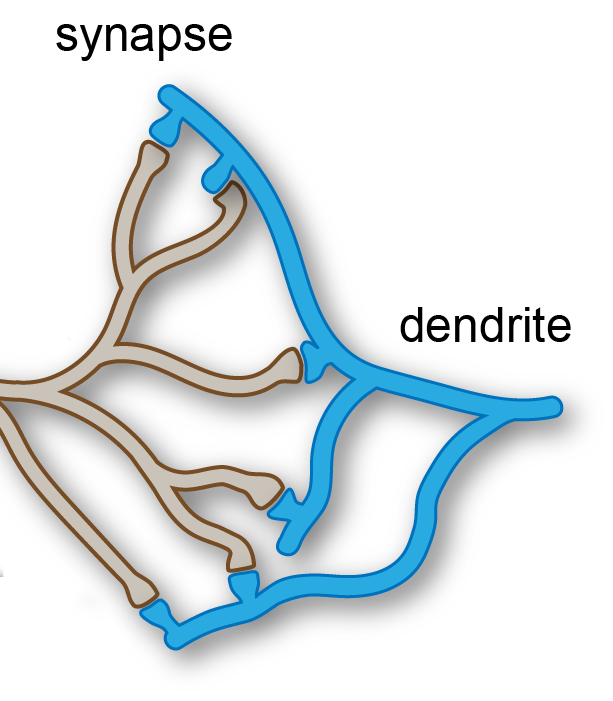

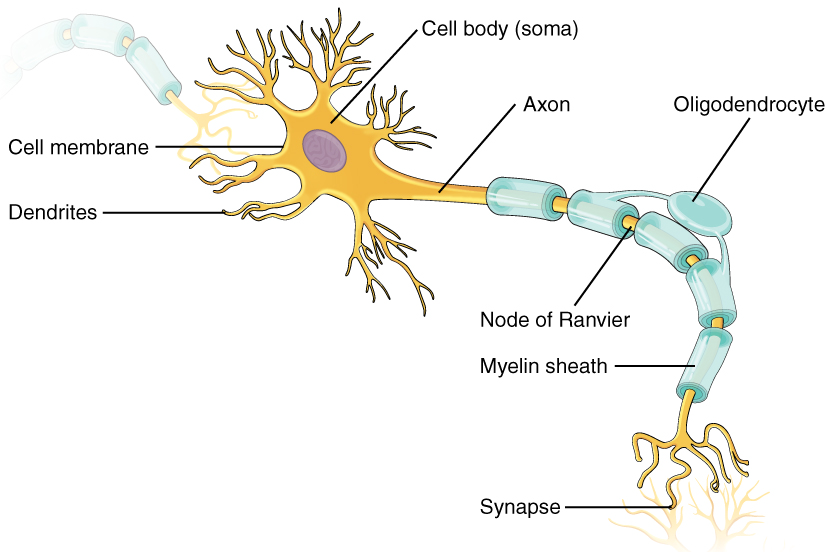

Neurons are the nervous system's workhorses, facilitating sensory perception, movement, and thought. Each neuron connects to up to 10,000 others via a tiny gap called the synaptic cleft (Byrne, 2013). This gap separates a neuron's dendrites (branch-like structures that receive signals) from the next neuron. Neurons communicate by releasing chemical messengers, called neurotransmitters, across the synaptic cleft. These chemicals bind to receptors on the receiving neuron, triggering electrical changes that carry the signal forward (Ludwig et al., 2023). The specific role of each neuron depends on its place within larger neural circuits, which govern functions like memory, reflexes, or emotions (Byrne, 2013).

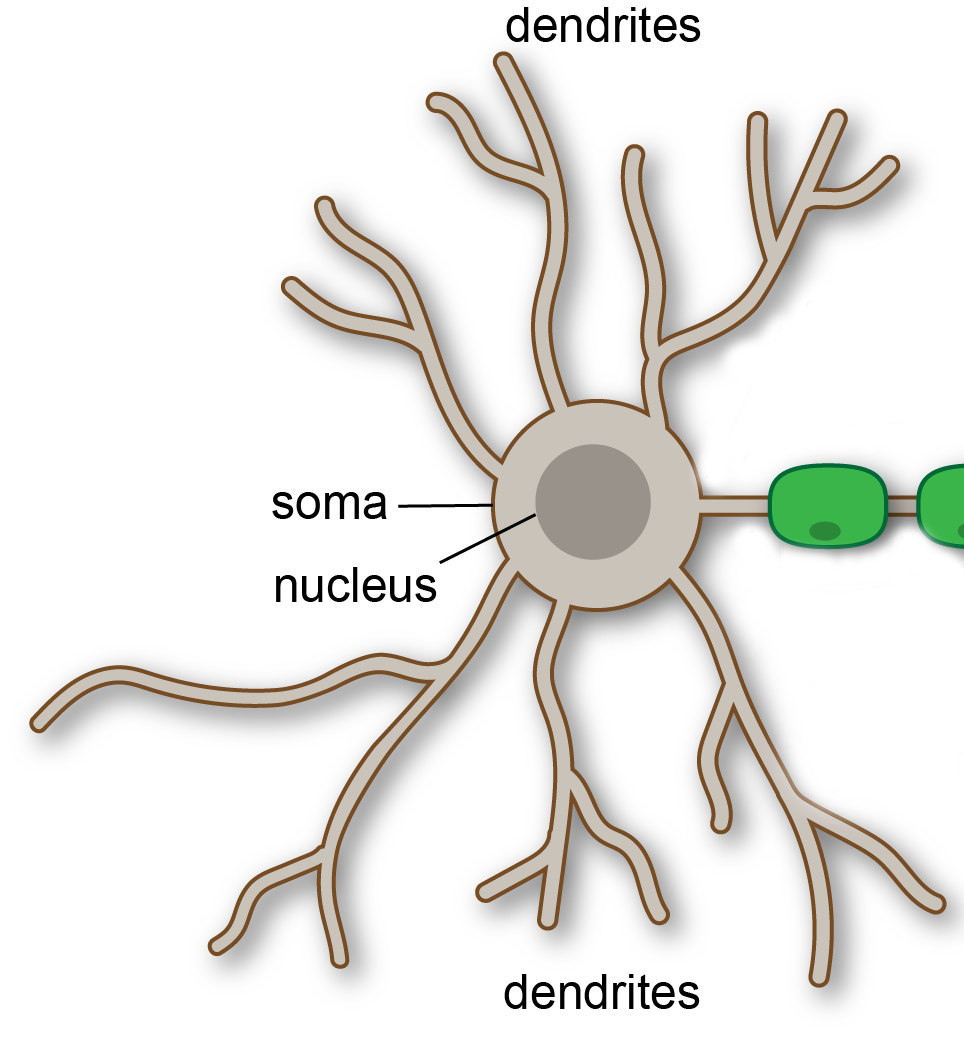

Soma (Body) Functionality

The soma, or cell body, is the neuron's hub, housing the nucleus and organelles—structures that act like a cell's organs, producing proteins, lipids, and enzymes essential for its function (Yu et al., 2020; Roney et al., 2022). The soma receives electrical signals (in the form of charged particles called ions) from neighboring neurons' dendrites. These signals are processed in the nucleus. If the incoming signals are strong enough, the soma's axon hillock—a specialized region—generates an action potential, a brief electrical surge (about +30 millivolts) that travels down the axon. If the signals are too weak, the neuron remains at its resting potential (around -75 millivolts), and no action occurs (Byrne, 2013).

When an action potential is triggered, the soma produces tiny packets called vesicles, which carry neurotransmitters. These vesicles travel to the axon hillock and down the axon to the neuron's terminal, ready to pass the signal to the next neuron (Budnik et al., 2016).

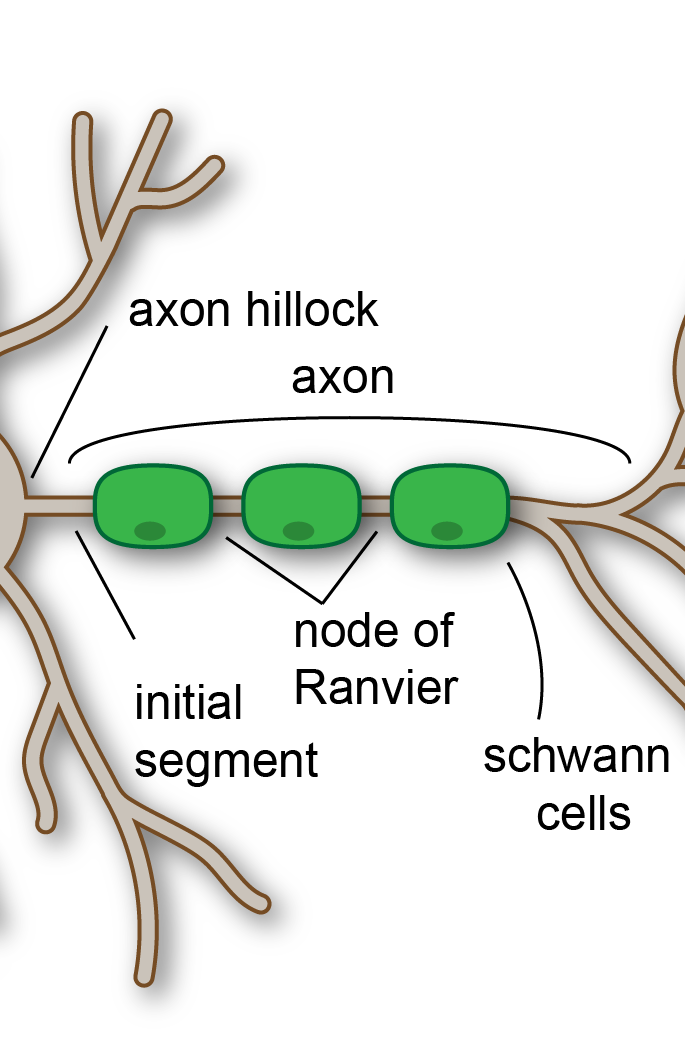

Axon Functionality

The axon is a long, slender extension that acts as a highway for transmitting signals from the soma to the neuron's terminal. Axons vary in length—some are just a millimeter, while others, like those in motor neurons, can stretch up to a meter (Byrne, 2013). Many axons are coated with a fatty layer called the myelin sheath, produced by Schwann cells (in the peripheral nervous system) or oligodendrocytes (in the brain and spinal cord). This sheath insulates the axon, speeding up signal transmission by allowing electrical impulses to "jump" between gaps called nodes of Ranvier (Arancibia-Cárcamo et al., 2017).

Axons also form intricate, fractal-like patterns, which optimize connectivity and efficiency in neural networks (Alves et al., 1996). These patterns allow neurons to communicate rapidly and reliably, supporting everything from reflexes to complex thoughts.

Terminal Functionality

The axon terminal is where the neuron's signal is passed to the next cell. When an action potential reaches the terminal, vesicles in a "resting zone" release their neurotransmitters into the synaptic cleft. This process is triggered by an influx of calcium ions, which causes the vesicles to fuse with the terminal's membrane and release chemicals like dopamine or serotonin (Scheller, 2013). These neurotransmitters cross the cleft and bind to receptors on the receiving neuron, potentially triggering a new action potential.

After release, empty vesicles are recycled back to the resting zone, ready for the next signal (Roos & Kelly, 2000). This continuous cycle ensures neurons can communicate repeatedly and efficiently, supporting rapid responses like pulling your hand away from a hot surface or feeling joy at a favorite song.

Functionality here is presented in the most basic form, and this applied when we receive information via our senses, cause us to feel our emotions and react accordingly via our nervous systems.

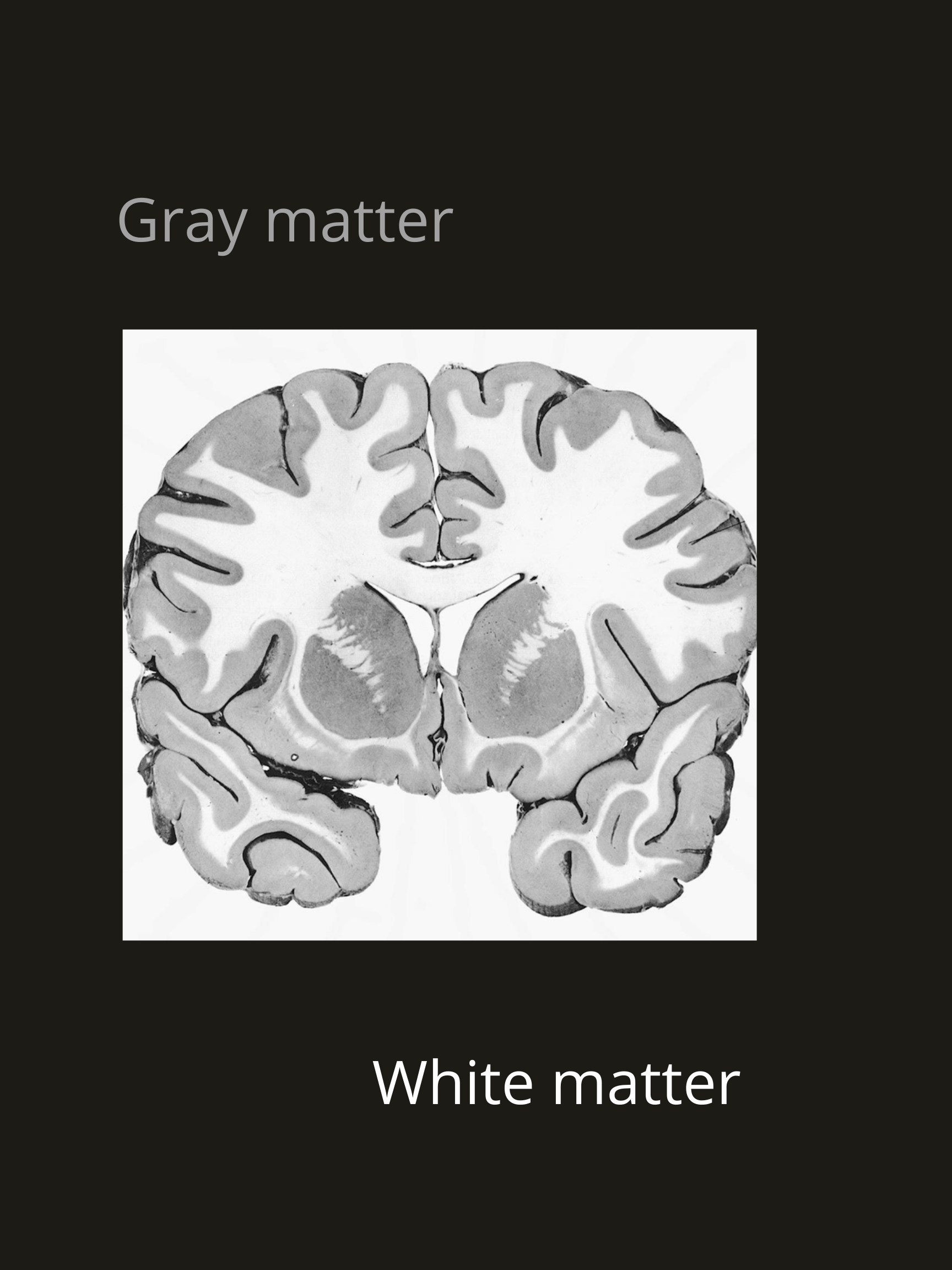

Gray and White Matter: The Brain's Functional Divide

Neurons are organized into two distinct types of tissue in the brain and spinal cord: gray matter and white matter. Gray matter consists primarily of neuron cell bodies (soma), dendrites, and unmyelinated axons, forming the brain's processing centers. It is where synapses occur, and neural computations—like decision-making, sensory processing, and memory formation—take place. Gray matter appears darker due to the high density of cell bodies and blood vessels (Mercadante & Tadi, 2020).

White matter, in contrast, is composed mainly of myelinated axons, which form the brain's communication pathways. The myelin sheath, produced by oligodendrocytes in the central nervous system, gives white matter its lighter appearance and enables rapid signal transmission between different brain regions or between the brain and spinal cord (Wycoco et al, 2013). For example, white matter tracts like the corpus callosum connect the brain's two hemispheres, allowing coordinated activities like speech and movement.

The interplay between gray and white matter is crucial for brain function. Gray matter processes information, while white matter ensures that signals travel efficiently to other regions.

Neurons are the foundation of our nervous system, enabling everything from basic reflexes to complex emotions and thoughts. By transmitting electrical and chemical signals, they allow us to perceive the world, make decisions, and interact with our environment. Understanding neurons not only reveals the mechanics of our brain but also underscores the remarkable complexity of human experience, from the spark of a single action potential to the intricate networks that shape who we are.

References

- Alves, S. G., Martins, M. L., Fernandes, P. A., & Pittella, J. H. (1996). Fractal patterns for dendrites and axon terminals. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, 232(1-2), 51-60.

- Arancibia-Cárcamo, I. L., Ford, M. C., Cossell, L., Ishida, K., Tohyama, K., & Attwell, D. (2017). Node of Ranvier length as a potential regulator of myelinated axon conduction speed. Elife, 6, e23329.

- Budnik, V., Ruiz-Cañada, C., & Wendler, F. (2016). Extracellular vesicles round off communication in the nervous system. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 17(3), 160-172.

- Byrne JH. Introduction to neurons and neuronal networks. Textbook for the Neurosciences. 2013 May:12. Available: https://nba.uth.tmc.edu/neuroscience/m/s1/introduction.html (accessed 27.09.2025)

- Ludwig, P. E., Reddy, V., & Varacallo, M. A. (2023). Neuroanatomy, neurons. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing.

- Mercadante, A. A., & Tadi, P. (2020). Neuroanatomy, gray matter. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL); 2025. PMID: 31990494.

- Roney, J. C., Cheng, X. T., & Sheng, Z. H. (2022). Neuronal endolysosomal transport and lysosomal functionality in maintaining axonostasis. Journal of Cell Biology, 221(3), e202111077.

- Roos, J., & Kelly, R. B. (2000). Preassembly and transport of nerve terminals: a new concept of axonal transport. Nature neuroscience, 3(5), 415-417.

- Scheller, R. H. (2013). In search of the molecular mechanism of intracellular membrane fusion and neurotransmitter release. Nature medicine, 19(10), 1232-1235.

- Wycoco, V., Shroff, M., Sudhakar, S., & Lee, W. (2013). White matter anatomy: what the radiologist needs to know. Neuroimaging Clinics, 23(2), 197-216.

- Yu, J., Manouchehri, N., Yamamoto, S., Kwon, B. K., & Oxland, T. R. (2020). Mechanical properties of spinal cord grey matter and white matter in confined compression. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials, 112, 104044.

Images for this article were collected from Wikimedia Commons. Images were slightly edited for use.