Building on our understanding of the Triple Network Model — where the Salience Network (SN) acts as a switchboard between the Default Mode Network (DMN) and Central Executive Network (CEN) — we now examine the more precise mechanisms that govern what we notice, when, and why: the Attention Networks.

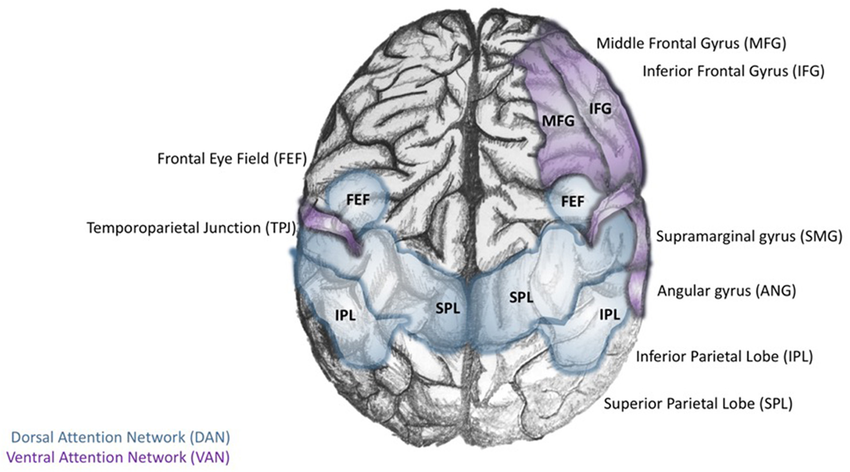

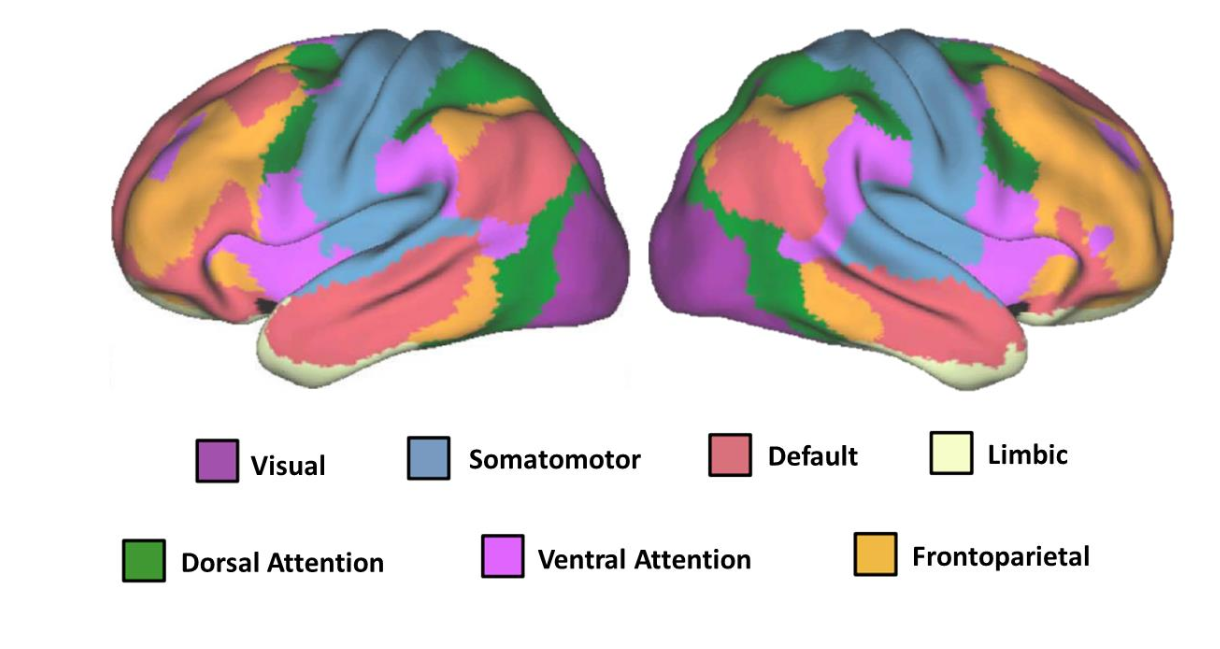

Attention is not a single process but a dynamic interaction between two major subsystems: the Dorsal Attention Network (DAN) and the Ventral Attention Network (VAN). Together, these networks coordinate goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention, allowing the brain to flexibly shift between focused concentration and reorient attention (Vossel et al., 2014).

Dorsal Attention Network (DAN)

The Dorsal Attention Network is responsible for top-down, voluntary control of attention — the process by which we deliberately focus on tasks or stimuli according to our goals and expectations (Corbetta & Shulman, 2002). This network activates when we search for an object, follow a moving target, or sustain attention on a demanding task.

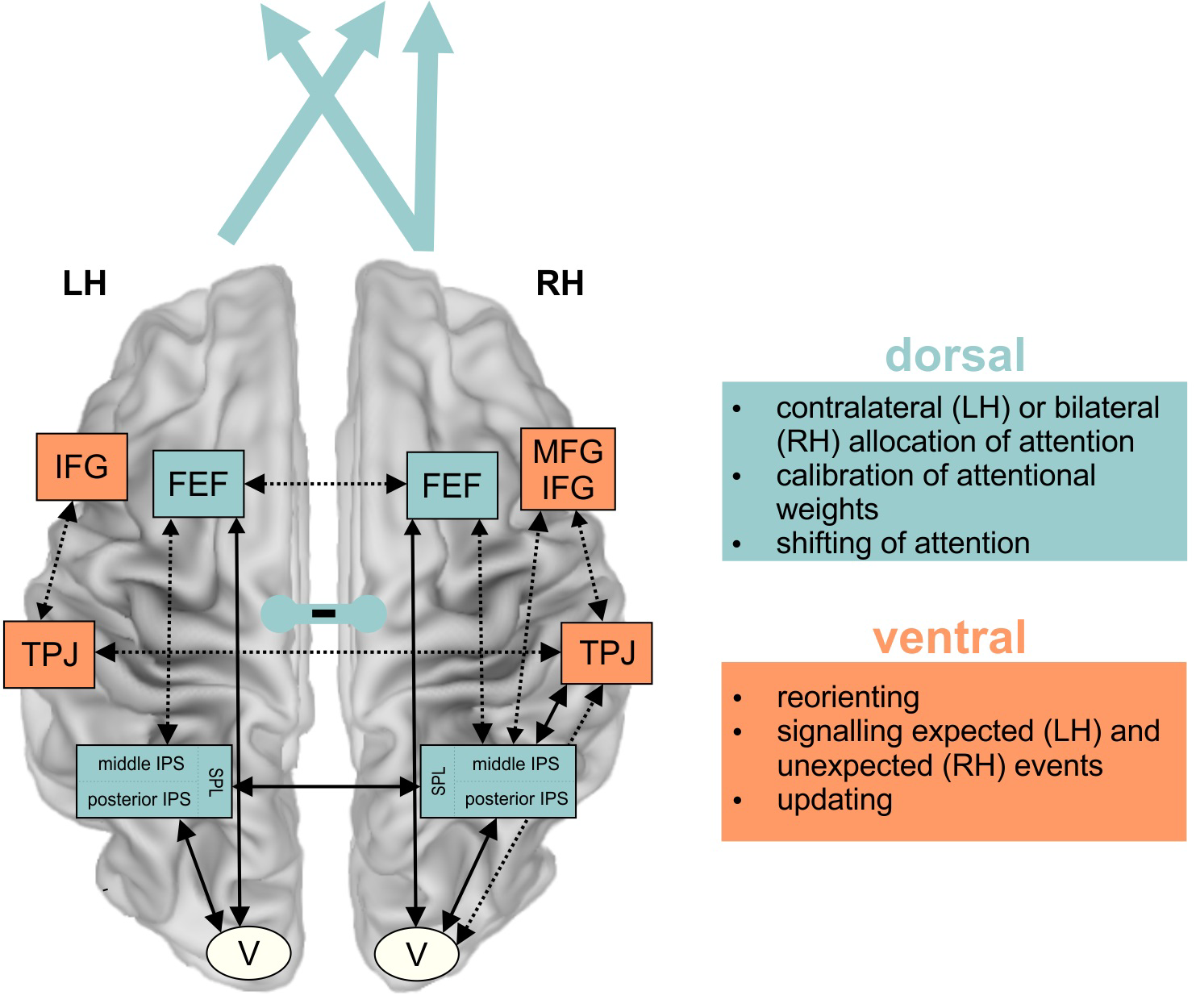

The primary regions involved include the Frontal Eye Fields (FEF) and the Intraparietal Sulcus (IPS), both of which guide the orientation of gaze and attention in space. The DAN maintains sustained focus by selecting relevant sensory input and filtering out distractions, ensuring cognitive resources remain directed toward the current objective (Petersen & Posner, 2012; Farrant & Uddin, 2015).

Functionally, the DAN operates in close coordination with the Central Executive Network (CEN) and the Salience Network (SN, Zhou et al., 2018). While the CEN provides cognitive control, the DAN maintains sensory focus, and the SN helps determine whether attention should remain stable or shift based on environmental cues.

The figure above illustrates the central nodes of the dorsal (light blue) and ventral (orange) attention systems and their interconnections. The visual cortex (V), shown in white, serves as a key sensory input region that interacts with both attention networks, supporting the integration of visual information necessary for attentional control.

Ventral Attention Network (VAN)

In contrast, the Ventral Attention Network mediates bottom-up, stimulus-driven attention — the brain's rapid and automatic response to unexpected or behaviorally relevant events.

This system activates when something suddenly captures our attention, such as a loud sound, movement in the periphery, or emotionally charged stimulus (Vossel et al., 2014; Farrant & Uddin, 2015).

Core regions include the Temporoparietal Junction (TPJ) and the Ventral Frontal Cortex (VFC), particularly the Inferior Frontal Gyrus (IFG). These areas work together to detect novelty or conflict and to reorient attention toward significant stimuli, interrupting ongoing top-down processing when necessary.

Integration of Dorsal and Ventral Systems

The DAN and VAN form a reciprocal attentional control system, constantly balancing stability with flexibility.

- The DAN sustains task engagement and goal-directed focus.

- The VAN monitors for novel or unexpected stimuli, ready to trigger a reorientation if something more relevant arises.

This interplay is coordinated by the Salience Network, which functions as a switchboard — determining whether to maintain focus (via the DAN) or to redirect attention (via the VAN).

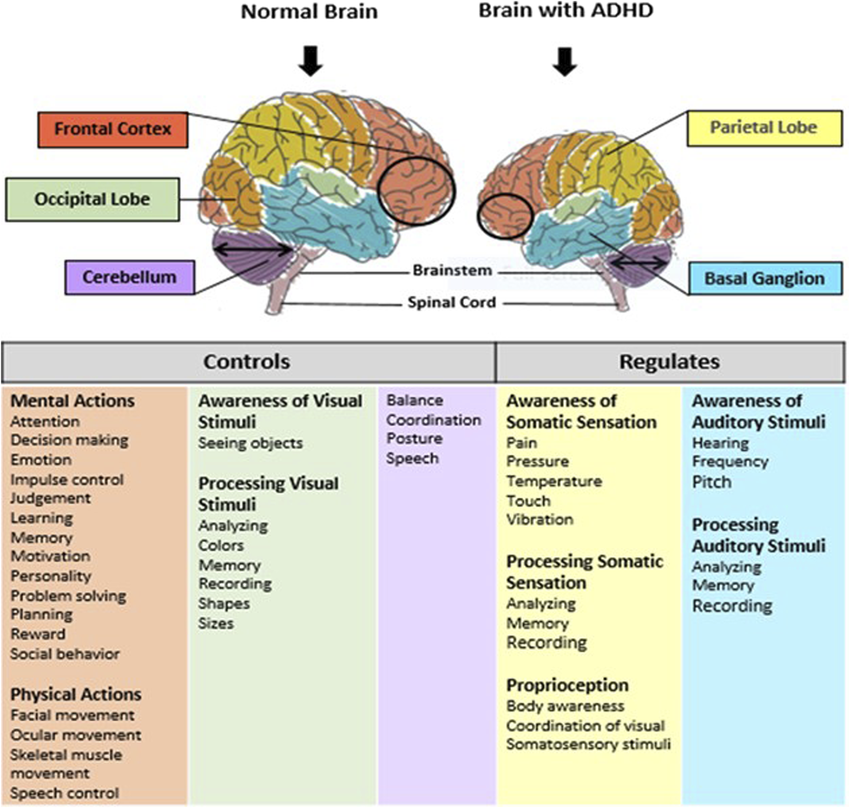

Disruption in this dynamic balance can lead to attentional instability and cognitive symptoms seen in disorders such as ADHD, anxiety, and traumatic brain injury, where either lack of attention or over-focused rigidity may occur (Evans et al., 2022; Barbey et al., 2015).

Clinical and Functional Relevance

Understanding the attention networks provides insight into both normal cognition and therapeutic interventions.

- Cognitive training and mindfulness practices lead to improvements in DAN function by strengthening sustained attention and goal maintenance (e.g., Froeliger et al., 2012).

- Therapies addressing trauma or anxiety often target VAN hyperactivity, helping reduce overreaction to unexpected or emotionally charged stimuli (e.g., Drysdale et al., 2023).

- Neurofeedback and neuromodulation can support the dynamic switching between DAN and VAN, improving attentional control and emotional stability (Mishra et al., 2021).

The DAN and VAN work as two sides of the same process: one focuses the mind, the other keeps it adaptive. Their coordinated operation allows for both stability and responsiveness — the foundation of efficient cognition and psychological flexibility.

Beyond its cognitive functions, attention serves as a relational mechanism — a way we connect with others. The same neural systems that allow us to focus, shift, and reorient in the world also underlie empathy and presence with others. When we cultivate balanced attention within ourselves and toward one another, we reinforce a sense of safety and mutual understanding.

In this light, respect and compassion become not just moral virtues, but neurobiological foundations for individual wellbeing and, in turn, the health of our communities. The neural networks that govern attention do not merely serve cognition — they bind us together.

References

- Barbey, A. K., Belli, A., Logan, A., Rubin, R., Zamroziewicz, M., & Operskalski, J. T. (2015). Network topology and dynamics in traumatic brain injury. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 4, 92-102.

- Corbetta, M., & Shulman, G. L. (2002). Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 3(3), 201–215.

- Drysdale, A. T., Myers, M. J., Harper, J. C., Guard, M., Manhart, M., Yu, Q., ... & Sylvester, C. M. (2023). A novel cognitive training program targets stimulus-driven attention to alter symptoms, behavior, and neural circuitry in pediatric anxiety disorders: pilot clinical trial. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 33(8), 306-315.

- Evans, T. C., Alonso, M. R., Jagger-Rickels, A., Rothlein, D., Zuberer, A., Bernstein, J., ... & Esterman, M. (2022). PTSD symptomatology is selectively associated with impaired sustained attention ability and dorsal attention network synchronization. NeuroImage: Clinical, 36, 103146.

- Farrant, K., & Uddin, L. Q. (2015). Asymmetric development of dorsal and ventral attention networks in the human brain. Developmental cognitive neuroscience, 12, 165-174.

- Froeliger, B., Garland, E. L., Kozink, R. V., Modlin, L. A., Chen, N. K., McClernon, F. J., ... & Sobin, P. (2012). Meditation‐state functional connectivity (msFC): strengthening of the dorsal attention network and beyond. Evidence‐Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2012(1), 680407.

- Genon, S., & Li, J. (2023). Brain networks atlases. In Advances in Resting-State Functional MRI (pp. 59-85). Academic Press.

- Mahrous, N. N., Albaqami, A., Saleem, R. A., Khoja, B., Khan, M. I., & Hawsawi, Y. M. (2024). The known and unknown about attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) genetics: a special emphasis on Arab population. Frontiers in Genetics, 15, 1405453.

- Mengotti, P., Käsbauer, A. S., Fink, G. R., & Vossel, S. (2020). Lateralization, functional specialization, and dysfunction of attentional networks. Cortex, 132, 206-222.

- Mishra, J., Lowenstein, M., Campusano, R., Hu, Y., Diaz-Delgado, J., Ayyoub, J., ... & Gazzaley, A. (2021). Closed-loop neurofeedback of α synchrony during goal-directed attention. Journal of Neuroscience, 41(26), 5699-5710.

- Petersen, S. E., & Posner, M. I. (2012). The attention system of the human brain: 20 years after. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 35, 73–89.

- Ross, J. A., & Van Bockstaele, E. J. (2021). The locus coeruleus-norepinephrine system in stress and arousal: unraveling historical, current, and future perspectives. Frontiers in psychiatry, 11, 601519.

- Vossel, S., Geng, J. J., & Fink, G. R. (2014). Dorsal and ventral attention systems: distinct neural circuits but collaborative roles. The Neuroscientist, 20(2), 150–159.

- Zhou, Y., Friston, K. J., Zeidman, P., Chen, J., Li, S., & Razi, A. (2018). The hierarchical organization of the default, dorsal attention and salience networks in adolescents and young adults. Cerebral cortex, 28(2), 726-737.