We have explored different brain regions from multiple perspectives. Now, it's time to understand how these networks interact with one another—and how they collectively shape our experiences, behaviors, and mental health.

We begin with the "habit network", the Basal Ganglia—a complex system of seven interconnected nuclei deeply involved in reward, learning, preparation, and timing (Chakravarthy et al., 2010). This network acts as a bridge between thought and action, influencing goal-directed behavior, motivation, motor preparation, working memory, and even our experiences of fatigue and apathy.

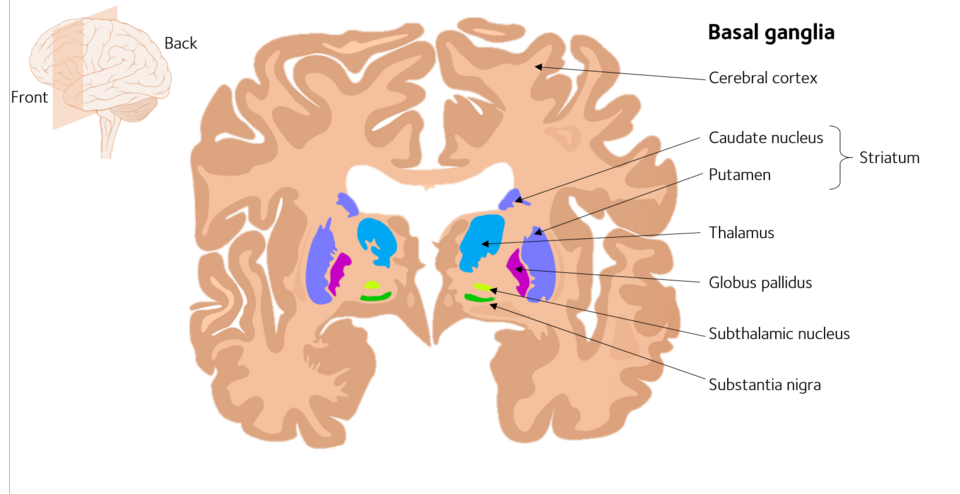

Striatum: Caudate and Putamen

The Caudate nucleus and Putamen together form the Striatum, the largest and most prominent structure within the Basal Ganglia. The Striatum is central to the reward system, driving motivation, reinforcement learning, and action planning.

By integrating information from various parts of the brain, it helps us optimize behavior through repetition, forming habits and refining motor skills over time (Graybiel & Grafton, 2015). In essence, the Striatum translates intention into consistent, efficient action—turning effort into instinct.

Globus Pallidus (Internal and External Segments)

The Globus Pallidus, divided into internal (GPi) and external (GPe) segments, acts as a major regulatory hub within the Basal Ganglia. The GPi serves primarily as an output nucleus, sending inhibitory signals to control movement precision and prevent unwanted actions. The GPe, on the other hand, plays a modulatory role, coordinating signals between other basal ganglia nuclei.

Together, they ensure that motor commands are smooth, balanced, and context-appropriate, preventing overactivation or underactivation of movement pathways.

Subthalamic Nucleus (STN)

The Subthalamic Nucleus serves as a key excitatory center, maintaining the delicate balance of activity within the Basal Ganglia. It is crucial for action selection and inhibition, essentially acting as a "brake" system to pause or adjust movements when necessary.

Dysfunction in this region has been linked to movement disorders such as Parkinson's disease, highlighting its role in maintaining motor control and behavioral flexibility.

Substantia Nigra (Pars Compacta and Pars Reticulata)

The Substantia Nigra is composed of two distinct parts:

- Pars Compacta (SNc): Produces dopamine, a neurotransmitter vital for reward learning, motivation, and movement regulation. Dopamine released from the SNc modulates activity in the Striatum, strengthening rewarding actions and facilitating learning through reinforcement.

- Pars Reticulata (SNr): Functions as another output nucleus, helping control eye movements and motor coordination by communicating with the thalamus and superior colliculus.

Together, these structures form the dopaminergic engine of the Basal Ganglia, powering learning, movement, and emotional drive.

Nucleus Accumbens

Often considered part of the ventral striatum, the Nucleus Accumbens is central to reward processing, motivation, and pleasure. It integrates emotional and cognitive inputs to drive goal-directed behaviors, translating desire into action.

The Nucleus Accumbens is heavily influenced by dopamine and plays a critical role in addiction, reinforcement learning, and the formation of positive habits—making it one of the key structures connecting emotion and behavior.

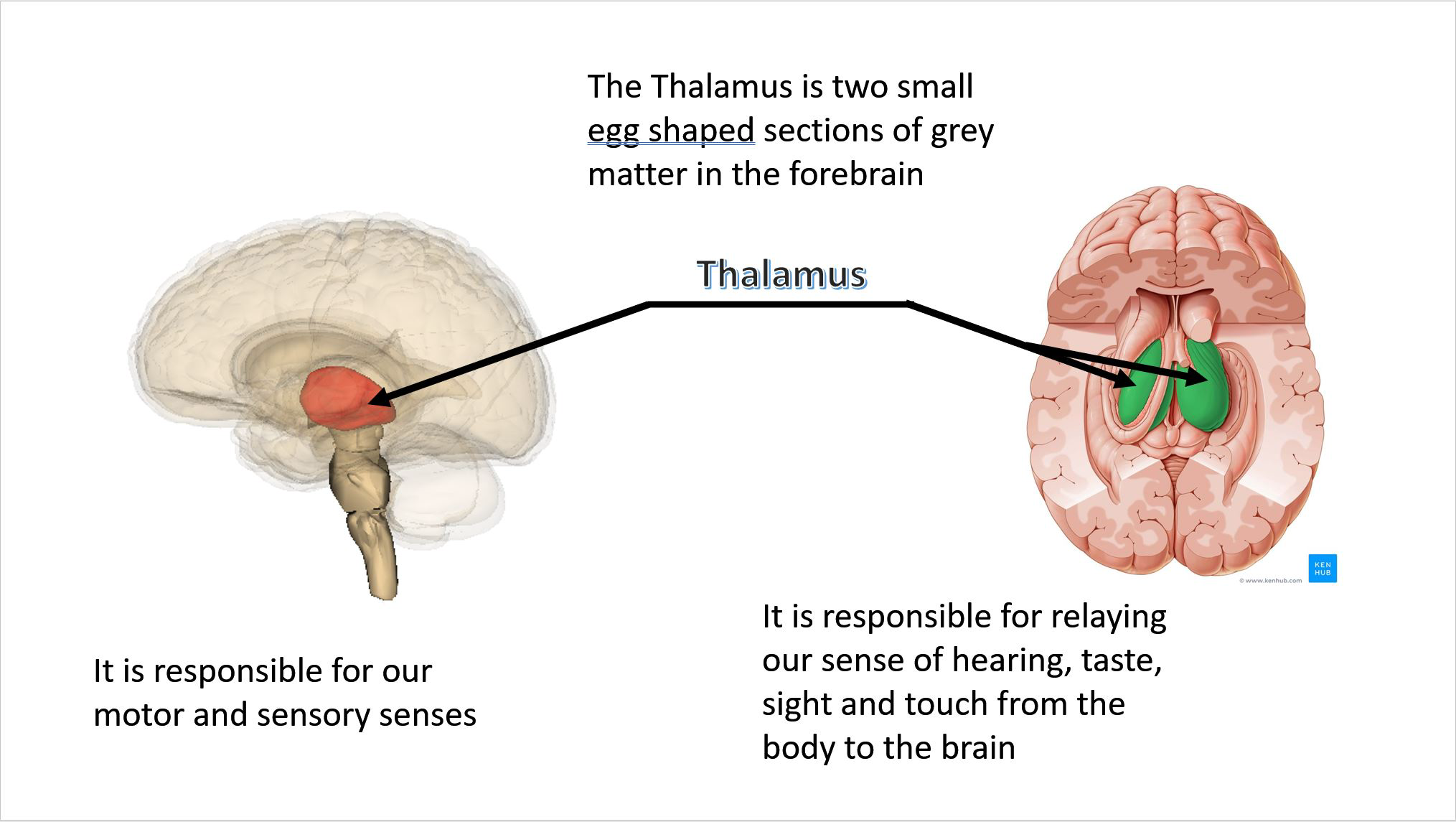

Thalamus and the Feedback Loop

The Thalamus acts as the relay and feedback center between the Basal Ganglia, cerebral cortex, and other brain regions. It receives processed signals from the output nuclei of the Basal Ganglia (such as the GPi and SNr) and sends refined information back to the motor and prefrontal cortices.

This creates a continuous feedback loop—a closed circuit in which the cortex initiates a plan or behavior, the Basal Ganglia refines and filters that signal, and the Thalamus sends the "approved" version back to the cortex for execution.

This loop allows the brain to select appropriate actions, suppress irrelevant ones, and adjust behavior dynamically based on reward feedback and experience.

There are several major loops involving the Basal Ganglia and Thalamus:

- Motor Loop: Governs voluntary movement and coordination.

- Associative (Cognitive) Loop: Involved in decision-making and working memory.

- Limbic Loop: Connects emotional and motivational states with behavior (involving the Nucleus Accumbens).

Through these loops, the Basal Ganglia–Thalamocortical system transforms raw motivation into organized, purposeful action, forming the neural foundation of habit, intention, and control.

Putting It All Together

The Basal Ganglia function as a coordinated network, linking thought, emotion, and movement. Whether we are learning a new skill, pursuing a goal, or falling into a familiar routine, this system continuously evaluates outcomes, rewarding successful actions and suppressing ineffective ones.

When functioning optimally, the Basal Ganglia enable fluid, goal-oriented behavior. When disrupted, they can contribute to a range of neurological and psychiatric disorders, from Parkinson's disease and Tourette's syndrome to OCD, addiction, and depression—reminding us just how integral habits and motivation are to mental health.

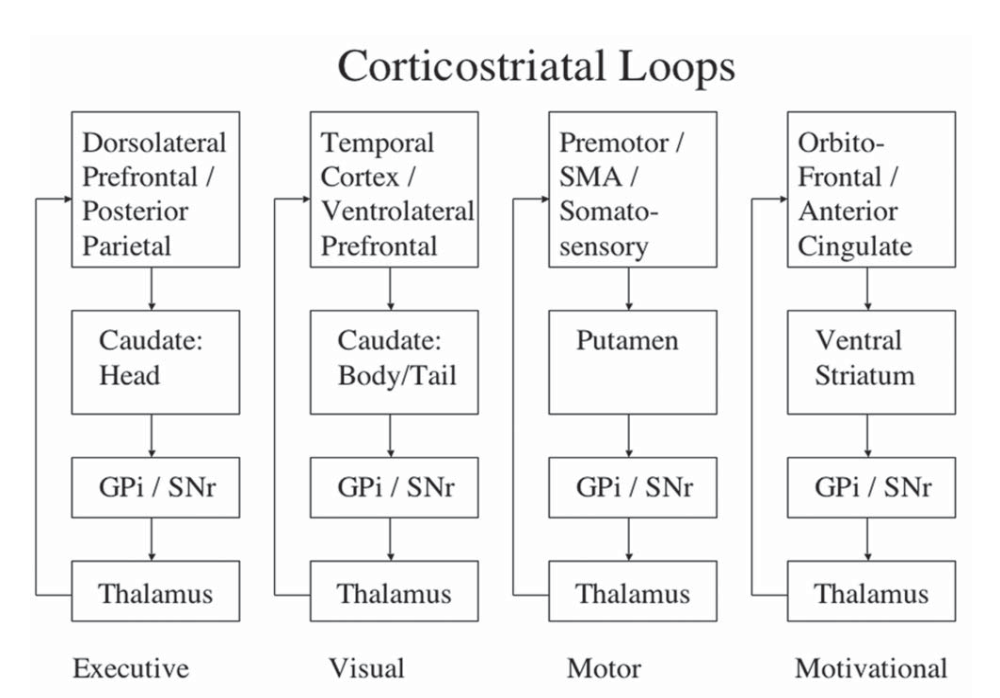

The diagram above illustrates four corticostriatal loops, showing how different regions of the cortex connect with specific areas of the basal ganglia and the thalamus to regulate distinct functions. The loops include:

- Executive loop: links the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex with the caudate head, supporting planning and cognitive control.

- Visual loop: connects temporal and ventrolateral prefrontal areas with the caudate body and tail, contributing to visual and associative processing.

- Motor loop: links premotor and somatosensory regions with the putamen, guiding movement initiation and coordination.

- Motivational loop: connects orbitofrontal and anterior cingulate areas with the ventral striatum, driving motivation and reward-based behavior.

References

- Chakravarthy, V. S., Joseph, D., & Bapi, R. S. (2010). What do the basal ganglia do? A modeling perspective. Biological Cybernetics, 103(3), 237–253.

- Graybiel, A. M., & Grafton, S. T. (2015). The striatum: where skills and habits meet. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 7(8), a021691.

- Haber, S. N. (2016). Corticostriatal circuitry. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 18(1), 7–21.

- Obeso, J. A., Rodríguez-Oroz, M. C., et al. (2008). The basal ganglia in Parkinson's disease: Current concepts and unexplained observations. Annals of Neurology, 64, S30–S46.

- Seger, C. A. (2006). The basal ganglia in human learning. The Neuroscientist, 12(4), 285–290.