According to the World Health Organization (WHO), stress can be defined as a state of worry or mental tension caused by a difficult situation. Stress is of course multidimensional and much more complex to convey, as each experience is idiosyncratic by nature. Acute stress responses act as a survival mechanism, directing the body's response according to what is experienced. Every single person reacts to different stressful situations according to their own idiosyncratic tendencies and personal past experiences, which is why so many types of therapeutic approaches are contemplated and each individual responds to different approaches (Bonta & Andrews, 2007).

There will be dedicated in-depth articles about stress and how to handle it, but it was deemed necessary to explore the sources of perception, how they form our experiences, and how stress can serve as either a savior or a detriment depending on the context. Our systems strive to maintain homeostasis, and stress acts as a response when our homeostasis is threatened (Chrousos, 2009).

Stress Typical Responses

Walter B. Cannon pioneered physiological research by recognizing that the sympathetic-adrenal medullary system would be the catalyst for an individual to move out of homeostatic balance (or resting potential) to respond during critical environmental situations (McCarty, 2016). Cannon first described the phenomenon in binary terms: "fight" or "flight". Fight refers to the idea that an organism would respond aggressively towards a threat or a crisis. Increased adrenaline will prepare muscles to stand ground, fight back, or even show threat or force in the hopes of scaring away a threat. On the other hand, the "flight" response refers to when an organism flees, escapes, or runs away from a threatening situation.

Recent literature suggested that a more complete description needed to be provided to encompass the complexity of acute stress responses. "Freezing" was associated with the flight response but was then segregated as a separate category. Freezing refers to the state of hypervigilance and being on guard during the presence of a stressor (Bracha, 2004). Prey that typically freezes increases the chances of survival by avoiding capture due to the visual cortex of mammalian predators evolved to detect movement effectively.

This differs from other reactive responses such as "Tonic Immobility", "fright", or simply playing dead. Even though the terms are used interchangeably in literature, there are some noticeable differences to mention (Bracha, 2004). Freezing acts as a "stop to see what is happening" mechanism, allowing an organism to respond, whereas "fright" refers to when an organism (i.e., opossums) uses such an opportunity to escape from a more mobile predator. Other tactics, like "fawn", involve pleasing or appeasing a threat in order to avoid any harm (Knight, 2025). Even though such tactics helped us developmentally (not only via our ancestors but also during our personal development—when do we have to flee a situation? Pause before reacting?), their exertion should be balanced with our logic, and we should not react to each threatening situation based solely on our emotions. Acute stress can develop into chronic stress, which can then cause a cascade of concerns for an individual (Guilliams & Edwards, 2010).

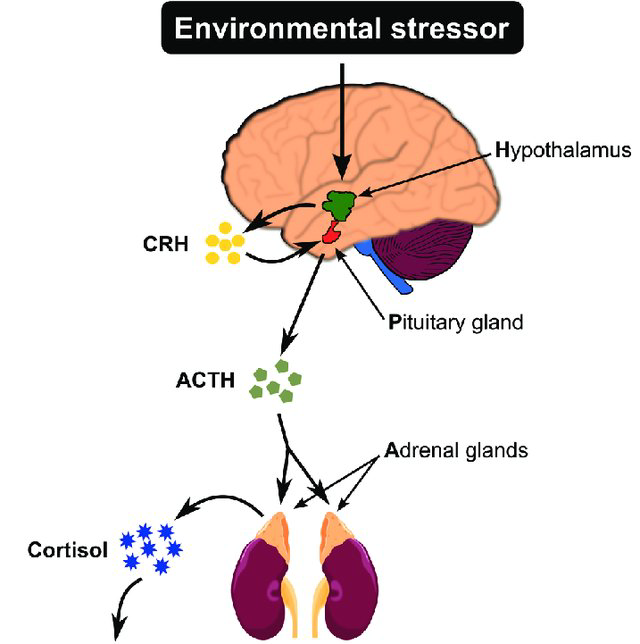

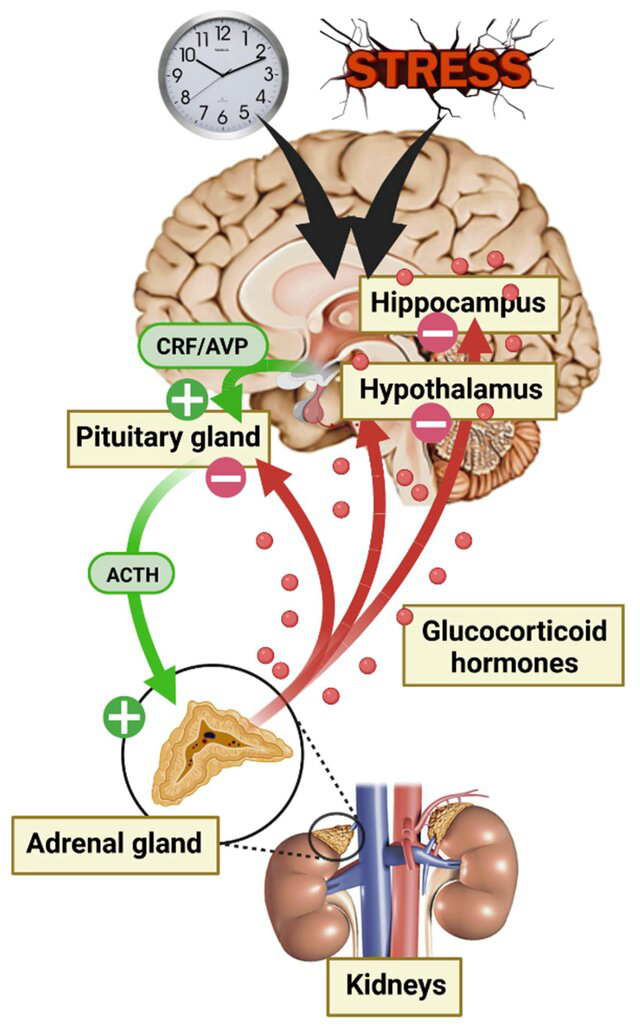

Here we come to the Hypothalamic Pituitary Axis (HPA), a subsystem within the endocrine system responsible for the secretion of cortisol and androgens, which in turn activate the stress response system (Saxbe, 2008; Goel et al., 2011; Guilliams & Edwards, 2010).

Main Areas

- Hypothalamus: The brain's control center which acts like the main link between the nervous and endocrine systems. When a stressor is detected, it releases Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone (CRH).

- Pituitary Gland: The master gland, important for growth and development. Receives CRH from the Hypothalamus during a critical event and in turn releases Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH).

- Adrenal Glands: ACTH travels to the adrenal glands located in the top most part of the kidneys. Adrenal glands in turn releases cortisol (primary stress hormone) to stimulate the body and mobilize energy as a stress response.

As the stress response system activates, the nervous system goes into alert and increases metabolism to initiate oxygenation of the blood, providing nutrition to the brain, heart, respiratory system, and muscles to supply energy (Chrousos, 2009).

Conditions Related to HPA Axis Dysfunction (Guilliams & Edwards, 2010)

| Increased activity of the HPA axis | Decreased activity of the HPA axis |

|---|---|

| Cushing's syndrome | Adrenal Insufficiency |

| Chronic stress | Atypical/seasonal depression |

| Melancholic depression | Chronic fatigue syndrome |

| Anorexia nervosa | Fibromyalgia |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | Premenstrual tension syndrome |

| Panic disorder | Climacteric depression |

| Excessive exercise (obligate athleticism) | Nicotine withdrawal |

| Chronic, active alcoholism | Following cessation of glucocorticoid therapy |

| Alcohol and narcotic withdrawal | Following Cushing's syndrome cure |

| Diabetes mellitus | Following chronic stress |

| Central obesity (metabolic syndrome) | Postpartum period |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder in children | Adult post-traumatic stress disorder |

| Hyperthyroidism | Hyperthyroidism |

| Pregnancy | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Asthma, eczema |

Conclusion

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis represents a sophisticated biological system that orchestrates our body's response to stress through a carefully coordinated cascade of hormonal signals. From the initial detection of a stressor by the hypothalamus to the release of cortisol from the adrenal glands, this axis ensures that our bodies can mobilize resources when faced with challenges. However, the complexity of stress responses—encompassing fight, flight, freeze, fright, and fawn reactions—highlights the nuanced ways in which individuals adapt to threatening situations.

The importance of maintaining system homeostasis cannot be overstated. When the HPA axis functions optimally, it helps preserve the delicate balance necessary for physical and mental well-being. However, as evidenced by the wide range of conditions associated with HPA axis dysfunction, disruptions to this balance can have profound consequences. Whether through chronic stress, hormonal imbalances, or other factors, deviations from homeostasis can contribute to various physical and psychological disorders. Understanding the HPA axis and its role in stress regulation provides crucial insights into how we can better support our body's natural capacity for adaptation and recovery, ultimately promoting long-term health and resilience.

References

- Bonta, J., & Andrews, D. A. (2007). Risk-need-responsivity model for offender assessment and rehabilitation. Rehabilitation, 6(1), 1-22.

- Bracha, H. S. (2004). Freeze, flight, fight, fright, faint: Adaptationist perspectives on the acute stress response spectrum. CNS spectrums, 9(9), 679-685.

- Chrousos, G. P. (2009). Stress and disorders of the stress system. Nature reviews endocrinology, 5(7), 374-381.

- Goel, N., Plyler, K. S., Daniels, D., & Bale, T. L. (2011). Androgenic influence on serotonergic activation of the HPA stress axis. Endocrinology, 152(5), 2001-2010.

- Guilliams, T. G., & Edwards, L. (2010). Chronic stress and the HPA axis. The standard, 9(2), 1-12.

- Knight, J. D. (2025). Is the nervous system sympathetic?. Journal of Surgery and Medical Case Reports, 2(2), 1-4.

- Lanoix, D., & Plusquellec, P. (2013). Adverse effects of pollution on mental health: the stress hypothesis. OA Evidence-Based Medicine, 1(1), 1-9.

- McCarty, R. (2016). The fight-or-flight response: A cornerstone of stress research. In Stress: Concepts, cognition, emotion, and behavior (pp. 33-37). Academic Press.

- Mennesson, M., & Revest, J. M. (2023). Glucocorticoid-responsive tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and its inhibitor plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1): relevance in stress-related psychiatric disorders. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(5), 4496.

- Saxbe, D. E. (2008). A field (researcher's) guide to cortisol: tracking HPA axis functioning in everyday life. Health psychology review, 2(2), 163-190.